What Camera Lens Focuses Closest?

Sun ascension over a field of lupines, Redwood NP, California. The focal length was 16mm, and the closest objects to the camera were the flowers at the very bottom of the frame, almost two feet from the lens. I used my hyperfocal-altitude shortcut to observe the optimum focus distance, by doubling the distance from the closest object and focusing at four feet. And then I stopped to downward to f/sixteen to get enough depth of field to brand both the foreground and background sharp. 16mm, three bracketed exposures at f/16, ISO 100, blended with Lightroom'due south HDR Merge.

In this contempo post I talked about the importance of having a solid, well-practiced field routine, then that y'all don't forget of import steps, and you'll exist less likely to panic when the light gets interesting.

One of the steps in my routine, focusing, deserves a little more attention, and so I'm going to cover that step in more than detail here.

(In that previous post I covered some of the basics about focusing and finding the hyperfocal distance. The next section repeats some of that information, but with additional details. If you don't want to go over that territory again, however, feel complimentary to skip downward to the section below called "When the Hyperfocal Distance Doesn't Utilize.")

Some Basics

Beginning, permit's assume that you want to go everything in focus (which probably applies to 99% of mural photographs). If everything in the photograph is far away, focusing can be easy. All the objects in the movie are substantially at infinity as far equally the lens is concerned, so the focus altitude for everything is the same. You tin can focus on any part of the frame, either manually or with autofocus, and exist sure that you're focusing at the right distance.

How far away am I talking about? That depends on the lens. Y'all probably know that it's easier to get everything in focus with wide-angle lenses than telephoto lenses. If yous're using a wide-angle lens (say 28mm or wider), it's safe to say that if everything in the photograph is at least 50 anxiety away, then you don't have to worry almost depth of field, and you can focus anywhere in the frame. With a 50mm lens that "safe" distance is about 100 feet. With a 100mm lens it's more than like 250 anxiety. (These distances employ regardless of the sensor size, or ingather factor. Just the bodily focal length matters.)

Upper Yosemite Fall and rainbow, Yosemite. Although I used a telephoto lens (145mm) for this photograph, the cliffs and waterfall were at least half a mile from the camera – substantially at infinity as far as the lens was concerned. So focusing was piece of cake; I could autofocus anywhere, knowing that every department of the photograph was at infinity, so the focus distance for everything was the same. And since the depth of field was minimal I could employ f/5.6, a fairly wide aperture, and withal be sure of getting everything in focus. 145mm, one/180th sec. at f/v.vi, ISO 200.

If there'southward something in the frame that's closer than that, yous have to be more careful about where you focus.

Let'south say you've composed a photograph with a 24mm lens, where the closest object to the photographic camera is three feet away, and the farthest object is at infinity. That's a lot of depth, even for a wide-angle lens, so precise focusing is critical. Where (at what distance) should you focus? The short answer is: somewhere in betwixt, and closer to the foreground than the groundwork. (There's more depth of field backside the spot you focus on than in front end, so focusing closer to the foreground will allow you to stretch the depth of field to encompass both the closest and uttermost objects.)

Can we go more precise than that? Absolutely. You lot could utilise a hyperfocal-distance chart or app, but I find these cumbersome and tedious.

You could employ an adage like, "focus a third of the mode into the frame," or "focus a 3rd of the way from the bottom of the frame." These both have grains of truth, and work some of the fourth dimension, but don't work at all for many situations.

Finding the Hyperfocal Distance

So nosotros need something better. Here'due south a shortcut that I use all the time: the hyperfocal altitude is approximately double the altitude from the closest object to the lens. And then if the closest object to the lens is three feet abroad, then the hyperfocal distance is six feet. If the closest object is 10 feet away, so the hyperfocal distance is twenty anxiety. Simple, right?

(Note that the hyperfocal altitude is the optimum focusing distance for getting everything in focus from the foreground to infinity. It doesn't apply to situations where the background isn't at infinity, similar if you lot're trying to get everything from x feet to 30 feet in focus. For those instances, see the section "When the Hyperfocal Distance Doesn't Apply" beneath.)

And so in the example in a higher place, if I'm trying to get everything from three feet to infinity in focus with a 24mm lens, where should I focus? I only double the distance from the closest object – three feet – and focus at vi anxiety. (You tin use the altitude scale on the lens for this, or but pick a spot six feet away and focus on information technology, either manually or with autofocus.)

Poppies, lupines, and oaks, belatedly afternoon, Sierra Nevada foothills, California. Once more I used my hyperfocal-altitude shortcut to find optimum focus distance. The closest objects, the flowers in the lower-right corner of the frame, were about iii feet from the lens, so I doubled that distance and focused at six anxiety. 17mm, ane/30th sec. at f/16, ISO 400.

At that place are limits of course. Even with a broad lens, like 24mm, I can't get everything from half-dozen inches to infinity in focus in one frame. Here are some practical limits for getting everything in focus with diverse focal lengths at f/xvi (the smallest aperture I'm willing to use before diffraction becomes objectionable). (I'm using a depth of field app to calculate this, with a circle of confusion of .02mm, which matches my practical experience with today'due south loftier-resolution sensors.)

16mm: 1.5 feet to infinity (at f/16, focused at 3 feet)

20mm: 2 feet to infinity (at f/16, focused at 4 feet)

24mm: 3 feet to infinity (at f/16, focused at vi feet)

35mm: 6 feet to infinity (at f/16, focused at 12 feet)

50mm: thirteen feet to infinity (at f/sixteen, focused at 26 feet)

100mm: fifty anxiety to infinity (at f/16, focused at 100 anxiety)

200mm: 200 feet to infinity (at f/16, focused at 400 anxiety)

You don't have to memorize this (though that wouldn't hurt). I'k just trying to show you the limits of what's possible. You're but not going to be able to everything from 10 anxiety to infinity in focus with a 100mm lens (at least not with i frame).

When the Hyperfocal Distance Doesn't Apply

The hyperfocal distance is the optimum focusing distance for getting everything in focus from the foreground to infinity. But what if the background isn't at infinity? What if you're trying to become a range from, say, 10 feet to 30 feet in focus?

Let's get back to one of those aphorisms for a minute – the one that says "focus a tertiary of the way into the frame." I can't come across how this axiom applies when the background is at infinity. For case, if the closest object to the camera is three feet away, and uttermost object 3 miles away, and then should you focus i mile away? No, of course not – that would be at infinity as far as the lens is concerned. You need to focus a lot closer than that.

Merely this precept is actually pretty accurate when when dealing with finite distances (in other words, when the far distance isn't infinity). For case, if you're trying to get a range from xx feet to l anxiety in focus, then focusing a third of the way between those ii distances would bring you to 30 feet, which is but almost right. You still take to estimate those distances, which I often find difficult, but it might at least get y'all into the ballpark.

What most that other aphorism, "Focus a third of the way from the bottom of the frame?" That idea also can work if you're photographing apartment ground that recedes into the altitude evenly (similar a meadow, field, playa, etc.) But if you have objects in forepart of other objects (like copse in front of other trees), it doesn't piece of work at all.

A Technique for Whatever State of affairs

Aspens in fog, White River NF, Colorado. I used the "quick-and-muddy method," described beneath, to detect the optimum focus distance for this scene. 70mm, 1/sixth sec. at f/16, ISO 200.

Instead, here's a technique I've been using for decades that works in whatsoever state of affairs, whether the range you're trying to make it focus is three feet to infinity, or three inches to nine inches. And information technology works fifty-fifty when you lot have objects stacked in front of each other.

The basic concept is pretty simple. Yous focus on the closest affair to the camera, then focus on the uttermost object, and and then center the focusing ring halfway in between those distances. Non halfway out in the field, but halfway between the altitude marks on the lens.

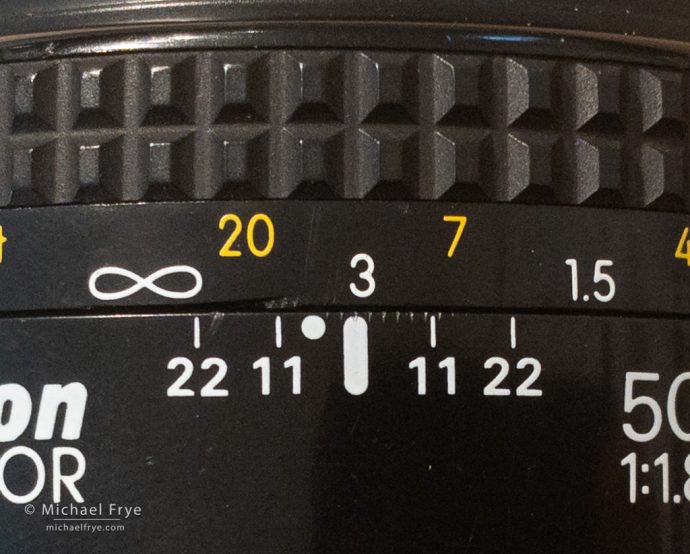

Allow'due south say I focus on the closest affair to the camera, and find out, according to the distance scale on my lens, that it'south seven feet away. So I focus on the farthest object, and see that it'due south xx anxiety away. To discover the optimum focusing point, I merely manually turn the focus band until it shows that I'one thousand halfway between the seven-foot marker and the 20-foot marking on the distance scale of the lens, like this:

If the closest object to the photographic camera is 7 feet away, and the farthest object is 20 feet away, then I focus halfway between those ii marks on the lens. In this case I ended up focusing just past the 3-meter mark, at approximately 11 feet.

What if the closest or farthest distances don't conveniently align with one of the foot or meter marks on the focusing ring? First, I focus on the closest thing to the camera, and mark that distance on the focusing ring with a fingernail. And then I focus on the farthest object, and marker that with some other fingernail. So I focus halfway between my fingernails, like this:

Instead of using foot or meter marks on the lens, you can just marker the closest and furthest points with your fingernails.

The Quick-and-Dirty Method

The technique I just described works really well if your lens actually has a distance scale. Unfortunately, many modernistic lenses don't. And so then what do yous practise? Try the "quick-and-muddy method."

Once more, utilise manual focus. Await through the viewfinder, and focus on the closest object to the camera. Next, focus on the farthest object from the camera. Then, still looking through the viewfinder, rock the focusing ring most halfway between those two distances. (Again, I'one thousand talking about the distance you're turning the focusing band, not the distance between objects in the field.)

Check yourself past seeing if the foreground and groundwork look equally out of focus. In other words, if the foreground looks sharper than the background, you've focused too close. If the background looks sharper than the foreground, you lot've focused as well far. If both the foreground and background expect equally fuzzy, then you've focused at the right distance. (I call this the Every bit Fuzzy Principal.)

Here'due south an case of the quick-and-muddy method. For this patch of flowers in our k I beginning focused on the closest thing to the camera – the flowers in the lower-left corner of the frame:

To apply the quick-and-dirty method you first focus on the closest affair to the camera – in this example, the flowers in the lower-left corner.

Side by side, I focused on the uttermost affair from the photographic camera – the flowers in the upper-right corner:

Next you focus on the farthest thing from the camera – hither, the flowers in the upper-right corner.

And then I rocked the focusing ring about halfway between, and checked to see if the foreground and background were every bit out of focus. Here, the flowers in the lower-left corner look almost as fuzzy as the flowers in the upper-right corner, so it looks like I'm focused in the correct spot:

Then yous rock the focusing ring about halfway in between, until the foreground and background expect near equally fuzzy.

Hither's a brusk video that demonstrates this technique:

(If you lot can't see the video, click here.)

I really utilise this quick-and-dirty method more often than mark the distances on my lens, even if my lens has a distance scale. Information technology's faster.

Even so, for this quick-and-dirty method to work the discontinuity has to exist wide open, otherwise information technology's hard to see what's in focus and what's not. This isn't a concern with SLRs, since the lens diaphragm stays open until you press the shutter. And then even if you have the aperture set up to f/16, the diaphragm will actually exist wide open at f/ii.8 or f/4 (or whatsoever your lens's widest discontinuity is) until you press the shutter. This wide-open viewing discontinuity makes the depth of field shallow, assuasive you to see what's in focus more readily.

Only with some mirrorless cameras the lens may really exist stopped down even earlier you press the shutter – depending on the camera and its settings. I can't get into detail about every camera here, but I'll mention that with a Sony mirrorless cameras and Sony lenses, the discontinuity is usually stopped down even before you press the shutter. So if y'all've set a smaller aperture similar f/11 or f/16 it becomes hard to see precisely where yous've focused, considering there's so much depth of field.

To change that y'all tin either but manually adjust the f-stop to your widest aperture to focus (and then reset it to have the picture), or, in the menu, under Live View Display, plow the Setting Result to Off, which makes the camera acquit like an SLR by keeping the diaphragm open until you printing the shutter. (Note that I recommend usually having the Setting Effect on, so that y'all become a live preview of your exposure. I put the Live View Display menu item in my Office menu for quick access, and then I can plow the Setting Effect off and back on when needed.)

Naturally, any of these techniques take practice. You lot tin do focusing in your lawn – and at present might be a skillful time to practise that.

Setting the Aperture

In one case you've establish the optimum focusing altitude, using any of the methods described above, then y'all demand to pick an discontinuity, take the picture, and bank check sharpness.

Picking the aperture is actually pretty easy. For 95% of my photographs I use either f/xi or f/16.

If everything in the scene is far enough away to be at infinity, then depth of field isn't an consequence. You could use any aperture, so you may too pick the f-stop where your lens is sharpest. For almost lenses that'southward in the middle range, somewhere between f/five.6 and f/11. I usually utilise f/11 to make certain I have enough depth of field. I might use f/eight or f/5.6 if everything is really far abroad, and I call back my lens will be sharper at one of those wider apertures.

If the scene has some depth to it – plenty depth to require focusing precisely, as described at length above – then I'll utilise f/16. That's the smallest discontinuity I'm willing to use before diffraction becomes objectionable. (For more almost that topic, see this post.)

Sand dunes, Mesquite Apartment Dunes, Expiry Valley. When a scene has some depth, like this 1, I typically utilise f/16 – the smallest aperture I'm willing to use before getting objectionable diffraction. Here the focal length was 33mm, and the closest thing to the photographic camera was the sand at the bottom of the frame, which was about 5 feet away. So I focused at double that distance (about 10 feet), and used f/16 to get sufficient depth of field. 33mm, 1/8 sec. at f/16, ISO 100.

Then take the picture, magnify the epitome on the dorsum of the photographic camera, and check to see if everything is in focus. If everything looks precipitous, great – you're done. If the foreground is sharp but the background is soft, so you've focused to close; accommodate your focus and try again. If the groundwork is sharp but the foreground is soft, then you've focused too far; adjust your focus and effort again. If the heart is sharp, but both the foreground and background await soft, then yous're focused at the right altitude, just yous didn't have sufficient depth of field. Effort using a smaller aperture, or, if that doesn't piece of work, you'll need to focus stack.

Plainly you need to set up your exposure mode to either aperture-priority or manual to perform this step!

So that's it. I know this is a lot to assimilate, but I wanted to exist thorough, and give yous a number of options so that you can pick what works best for you. Proficient luck – and don't forget to exercise!

— Michael Frye

Related Posts: Developing a Solid Field Routine; Focus-Stacking Season; Why F/xvi?

Michael Frye is a professional photographer specializing in landscapes and nature. He is the writer or primary photographer of The Photographer's Guide to Yosemite, Yosemite Meditations, Yosemite Meditations for Women, Yosemite Meditations for Adventurers, and Digital Mural Photography: In the Footsteps of Ansel Adams and the Great Masters. He has also written three eBooks: Light & State: Landscapes in the Digital Darkroom, Exposure for Outdoor Photography, and Landscapes in Lightroom: The Essential Step-past-Step Guide. Michael has written numerous magazine articles on the art and technique of photography, and his images take been published in over thirty countries around the world. Michael has lived either in or well-nigh Yosemite National Park since 1983, currently residing just outside the park in Mariposa, California.

Source: https://www.michaelfrye.com/2020/04/20/how-to-get-everything-in-focus/

Posted by: shawpuble1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Camera Lens Focuses Closest?"

Post a Comment